From Isolation to Obsession: How Loneliness Negatively Translates on Social Media

As a result of the loneliness epidemic, new communities have emerged, many shaped by the echo chambers of social media. Technology has transformed the way we connect, but for many, it's become a substitute for real-life relationships rather than a bridge to them. Prolonged isolation, worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic and a growing disconnection from traditional support systems, has led to a rise in "chronically online" individuals, people who spend most of their social and emotional lives on the internet. In these virtual spaces, distorted ideas of beauty, masculinity, and self-worth circulate freely and often go unchallenged. Communities form not around healing or growth, but around shared grievances, insecurities, and resentment.

Among the more concerning of these digital subcultures are incels, or involuntary celibates, a term referring to people who believe they are unable to access sex or romantic relationships due to immutable traits such as their genetics, facial structure, or social status (Radicalisation Awareness Network, 2021). While loneliness and rejection are nearly universal human experiences, the incel community takes these feelings and, through isolation and online radicalization, transforms them into deep resentment, often directed at women, attractive men, and society as a whole.

Much of this discontent is exacerbated by the rise of online fitness culture. Originally intended to promote wellness, the modern fitness community has, for some, become a rabbit hole of unattainable goals. Individuals are lured in with the intent of self-betterment, only to find themselves obsessing over hyper-specific traits like “hollow cheeks,” jawline definition, clear skin, and the elusive shredded physique. These body ideals aren’t just unrealistic—they’re increasingly linked to a growing subculture called gymcels, fitness-focused men who internalize incel ideology under the guise of “self-improvement.”

To better understand this convergence between fitness and incel identity, I spoke to a man who posts radical fitness content on TikTok. He’s someone I’ve known for a while and who has been immersed in the gym space for years. While I am not accusing him of being an incel, I was curious to hear how someone active in this community perceives its potential for toxicity and ideological drift.

Question:

- What led you to wanting to become a part of the fitness community?

Response:

- “I think honestly trying to spread healthy eating and healthy habits. But like one of the videos was making fun of a certain group inside the fitness community”

- I am not accusing this individual of being an incel, I just simply want to know his thoughts on all of it, as he has been a part of the fitness community for as long as I have known him. Being a part of a community for an extended period of time might have exposed him to people transitioning in and out of these toxic mindsets.

Question:

- Do you think this community can become toxic at all? Do you think that falling too deep into it can turn boys into incels?

Response:

- “…I’m actually writing a research paper on the gym community being toxic”

- “Yes I think people mostly guys in general turn into incels…I uploaded a few videos on Tik tok. They did pretty well. One in particular I focused on in the paper was one about the looks maxing community which are incels. They try to get like proper facial proportions…[some] comments I had to delete because they were so hateful towards others.”

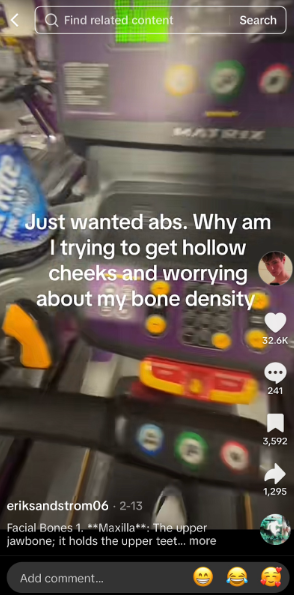

This connects directly with the growing phenomenon of looksmaxxing, a term that describes extreme methods (including surgery and drug use) to enhance facial aesthetics, particularly among young men convinced that beauty is the only ticket to love and acceptance. In this world, even “just wanting abs” snowballs into panic about bone density and buccal fat (Dabb, 2024). One of his TikToks illustrates this descent perfectly: “Just wanted abs. Why am I trying to get hollow cheeks and worrying about my bone density?” The video now has over 32.6K likes, a signal that this bizarre spiral is far from niche.

The Radicalisation Awareness Network found that mental health issues like anxiety and depression are rampant in incel communities, particularly among young men who experience relational trauma or social exclusion (RAN, 2021). For some, the gym becomes a way to reclaim power. For others, it becomes a site of obsession, shame, and comparison. Instead of solving their problems, gymcels spiral further into the belief that they are doomed to be unloved unless they become someone they’re not. Obsessing over these things can become physically unhealthy even. Another one of his tik toks shows a shopping cart filled with “lower calorie” and “zero sugar” items, which are not adequate replacements for the real thing nutritionally.

Even more troubling is how gymcel culture reinforces an external locus of control, the belief that one’s circumstances are controlled entirely by outside forces like genetics or society. This mindset is common among incels, who often blame women, “Chads,” or capitalism itself for their problems (RAN, 2021). The Thred article emphasizes how this narrative is particularly appealing in a culture that increasingly commodifies appearance and values hypermasculinity (Dabb, 2024).

So what now? To be clear, not everyone in the fitness community is an incel, and most people just want to feel better in their bodies. But it’s essential to recognize how certain online spaces, even ones seemingly focused on health, can morph into echo chambers of insecurity and hatred.

Preventing this doesn’t mean discouraging fitness,it means promoting a more inclusive and holistic idea of what it means to be “healthy” and “attractive.” That includes:

De-stigmatizing mental health support.

Promoting alternative narratives of masculinity.

Highlighting diverse body types and real-life relationships.

Encouraging young men to develop identities beyond appearance.

The goal shouldn’t be to chase hollow cheeks or impossible aesthetics. It should be to feel confident and self-fulfilled.

References:

Radicalisation Awareness Network. (2021, July 28). The incel phenomenon: Exploring internal and external issues around involuntary celibates. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network_en

Dabb, A. (2024, March 13). The dangers of gymcel culture. Thred. https://thred.com/change/the-dangers-of-gymcel-culture/